Introduction to Design (tutorial)

Whether a poster, webpage, app, book cover, or any other visual composition “looks good” to the untrained eye is usually a reflection of how well that design uses visual principles.

These principles have remained largely unchanged for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. That’s because visual principles aren’t about aesthetics — they’re about how people see, and how we interpret visual information.

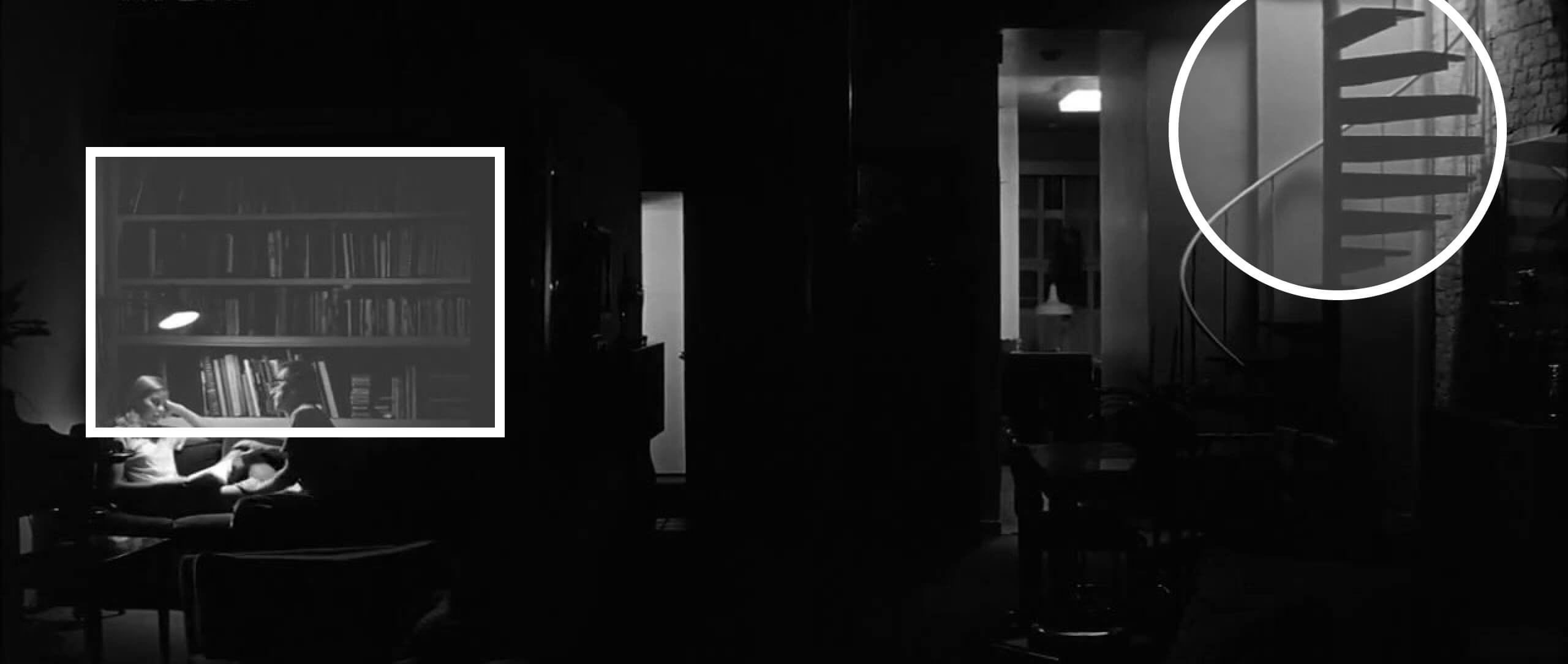

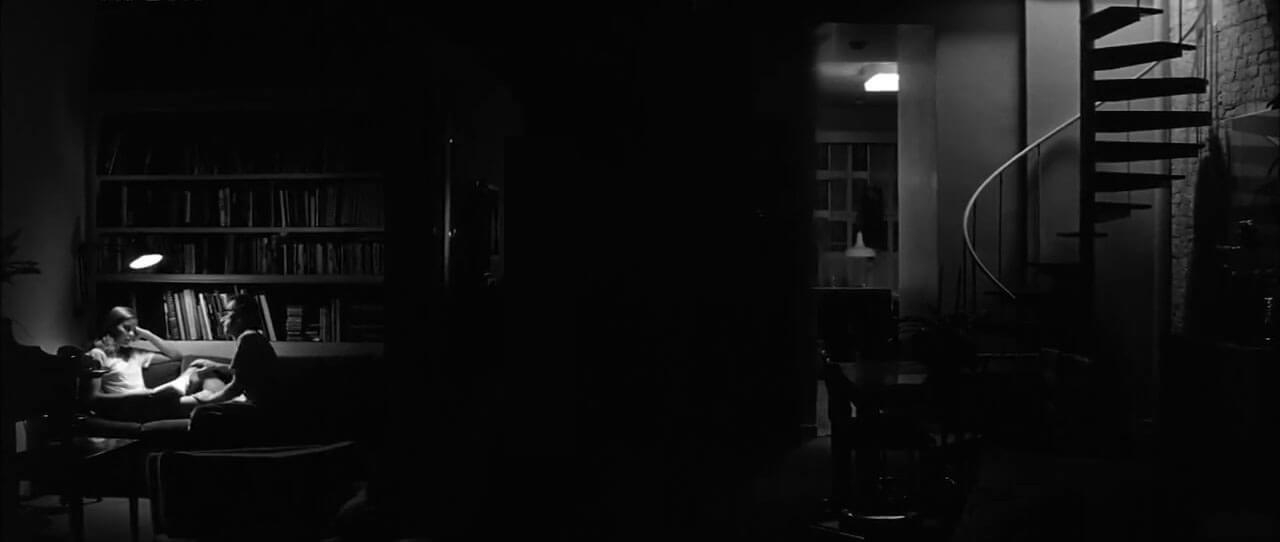

In this tutorial, we’ll examine visual principles in detail, and see how they apply to this famous scene from the film “Manhattan” (1979):

Principle 1: Proximity and grouping

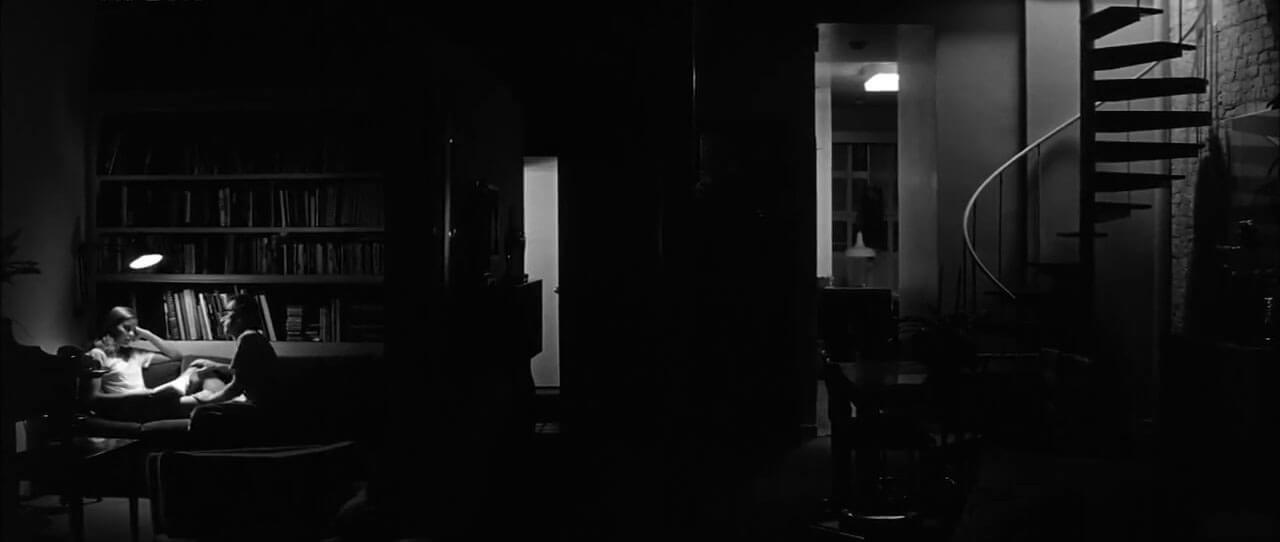

People tend to see things that are in proximity to one another, or that share similar characteristics, as groups. In the image below, we naturally see two groups of squares before we see nine squares, four squares, or thirteen squares.

Grouping by proximity

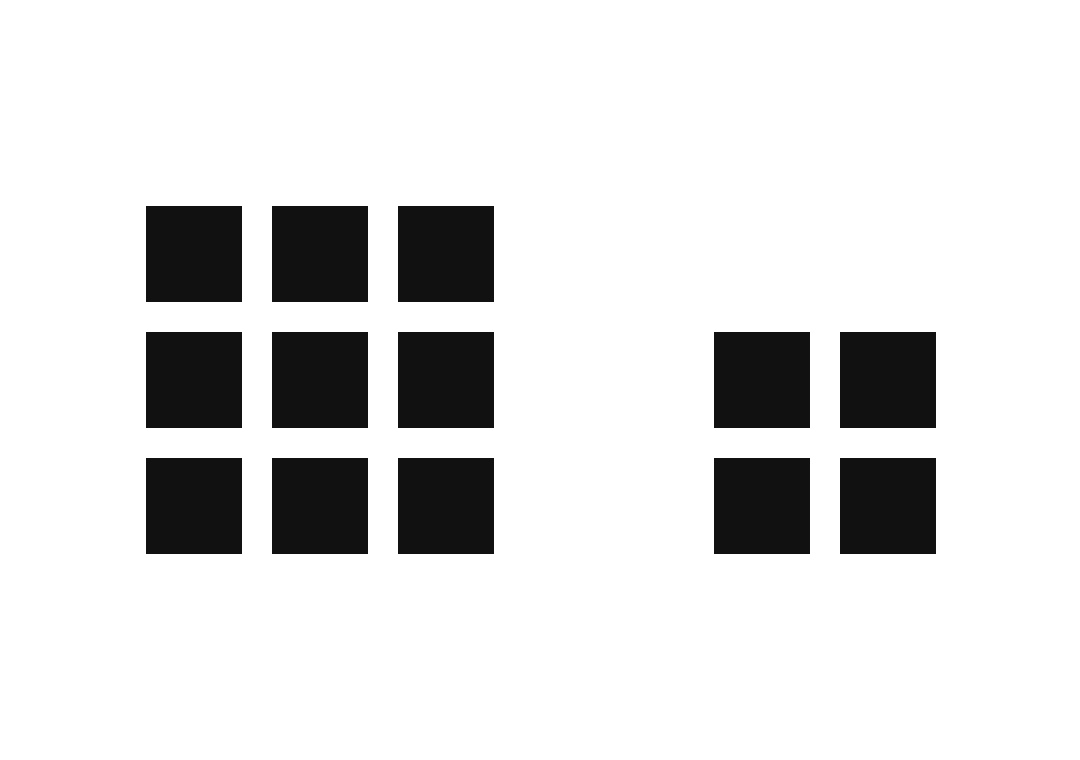

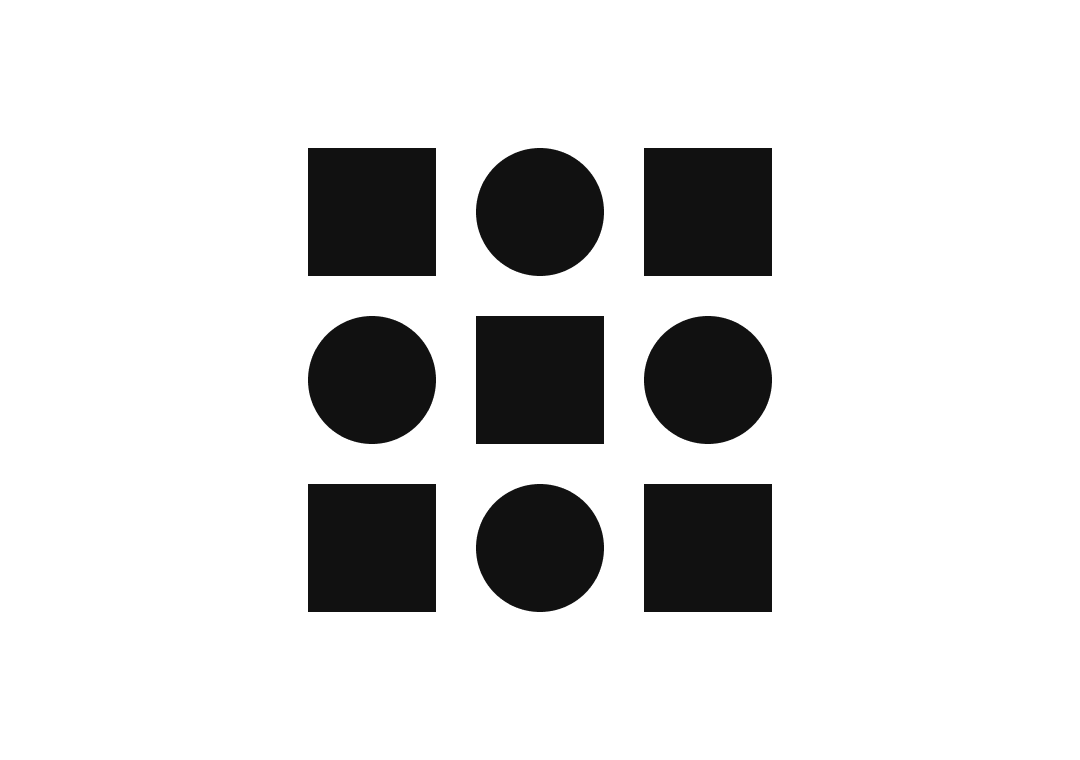

Similarly, the eye will group together elements that share characteristics like shape, size, and color.

Grouping by shape

Grouping by size

Grouping by color

In the film scene, there is proximity between the two people (and the reading lamp), forming a group.

There are also a few other groups in this scene. How many can you find?

These three foreground elements form a visual group

Principle 2: Visual hierarchy

Visual hierarchy is about the relative visual prominence of different elements in a layout.

If the eye is immediately drawn to something in a design — a headline, for example — that element is said to be “high” in the visual hierarchy. If an element is one of the last things the eye travels to — perhaps a page number — it is said to be “low” in the visual hierarchy.

Here’s an example:

Visual hierarchy is created by the interplay of a number of factors, including:

- Size. Larger elements tend to attract more attention.

- Position. Western readers are used to “starting” in the top-left of a page, and then following a line down the left edge.

- Light and dark. A dark area on a light background attracts attention, as does a light area on a dark background.

- Surrounding space. The more space there is around an element, the more prominent it tends to be.

Visual hierarchy isn’t an exact science, particularly in more complex layouts. Someone’s attention can usually be directed to the first and second areas of focus, but after that, their visual journey can get less predictable.

In the film scene, the large area of light in the top-right probably attracts our attention first, and the smaller area of light in the bottom-left second. However, this hierarchy is quite subtle, creating a level of visual tension (and reflecting, perhaps, the tension in the conversation).

Visual hierarchy between two areas of lighting

Principle 3: Spacing

“Design is as much an act of spacing as it is of making.”

— Ellen Lupton, designer, writer, curator, and educator

Spacing in design is similar to the spaces between notes, phrases, and movements in classical music. Just as music is made up of gaps and pauses as well as sounds, design is composed of visual spaces as well as visual elements.

Spacing serves a number of purposes. Where there is a lot of content, space is an important tool for breaking it up, organising it, and making it easier to absorb. And going back to the first principle in this list, spacing is what allows us to create visual groups.

For example, the image below shows a mockup of a book spread without any spacing. To organise the text, we can create visual groups simply by adding space before and after each heading, and by adding space to the first line of each paragraph.

Some text without any spacing

The text with spacing added

Where the spacing was applied

In the film scene, there is a large area of space in the centre, which helps guide our attention to the two areas of focus identified in the previous point. Can you find other ways that spacing is used in this scene?

Principle 4: Alignment

Alignment is about how different visual elements line up with one another (and about how they don’t).

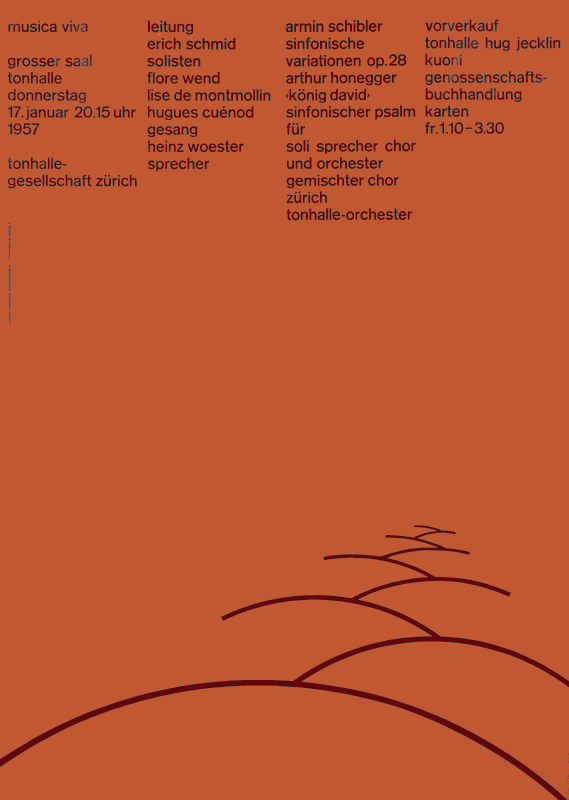

Josef Müller–Brockmann was perhaps the greatest advocate of alignment using a grid. The secret to his work was to limit himself to just a few key points of alignment in each layout.

For example, in the poster design below, there are six main points of alignment: the top margin, and the five column edges.

A poster design by Josef Müller-Brockmann

The main points of alignment

In the film scene, there is diagonal alignment between the two people, which reflects both the diagonal, right-to-left visual hierarchy, and the uneasy hierarchy in the relationship between the two characters.

Also note how the diagonal alignment here contrasts with the many horizontal and vertical lines within the scene.

Diagonal alignment between elements

Principle 5: Contrast

Contrast is about combining different sizes, colors, and styles to support visual structure, and often to create visual drama. A few examples are illustrated below.

Size contrast: big and small

Color contrast: bright and muted

Type contrast: decorative and direct

Texture contrast: rough and flat

In the film scene, there is contrast between the many horizontal and vertical lines. This is also an example of the seventh principle in this list, repetition.

Contrast between repeated vertical and repeated horizontal lines

Principle 6: Balance

Balance can be created either symmetrically or asymmetrically. Symmetrical balance is straightforward, but it can also be visually boring:

Symmetrical balance

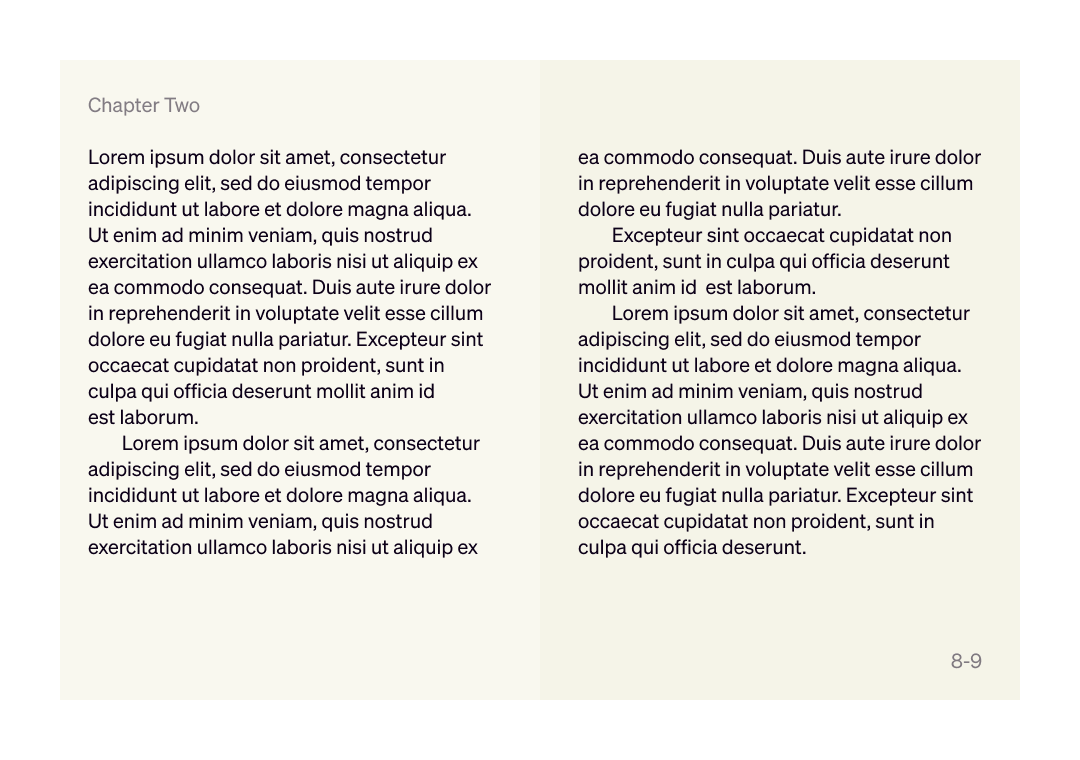

Asymmetrical balance tends to be more visually exciting, and it can be achieved in quite understated ways. For example, in the book mockup pictured below, the chapter number and page number provide subtle asymmetrical balance.

Asymmetrical balance

In the film scene, there is asymmetrical balance between the two main areas in the visual hierarchy.

Asymmetrical balance between two areas of lighting

Principle 7: Repetition and consistency

Repetition allows the eye to identify patterns and understand information. Standard book designs use some simple forms of repetition: the same layout for each page, the same layout for the first page of each chapter, and so on.

Other common forms of repetition include:

- repetition of colors, resulting in color palettes

- repetition of style through elements like text, illustrations, and icons

- repetition of shapes and patterns

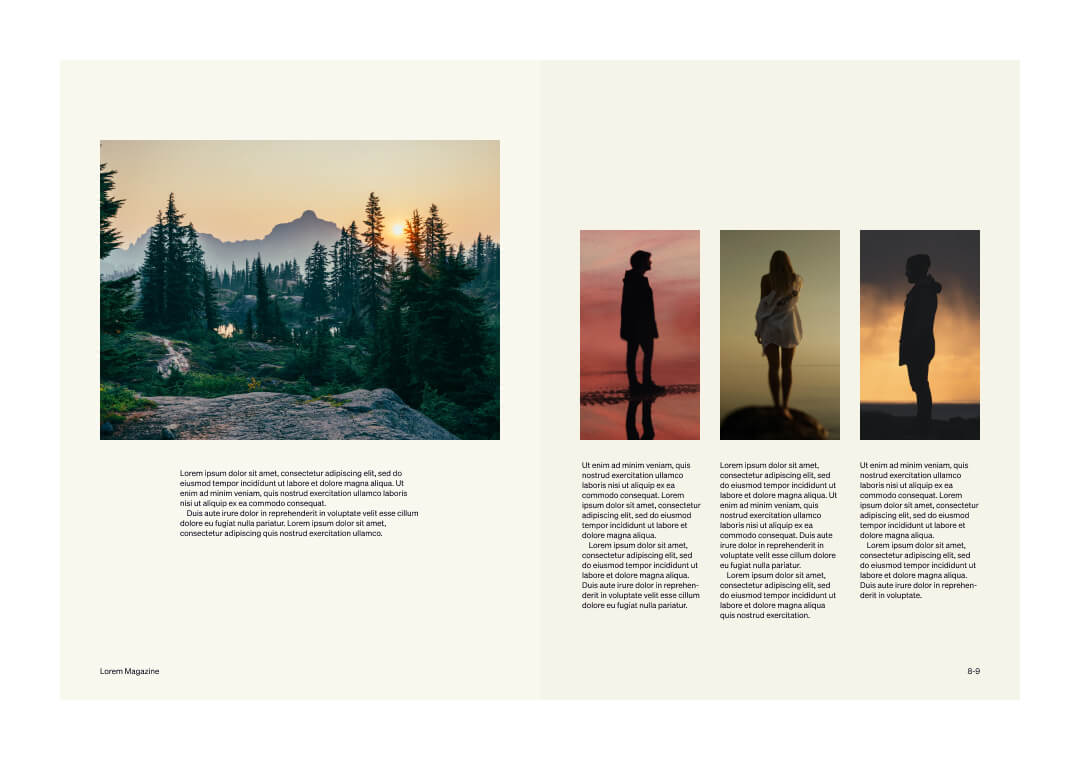

The right-hand page in the example below shows how repetition can be used in editorial design:

Repetition of elements on the right-hand page

In the film scene, both the staircase and the bookshelves create repeated horizontal lines. In turn, these also form groups.

Repetition of horizontal lines

Principle 8: Pacing

Pacing is a more subtle visual principle, which usually applies across multiple pages or screens.

It’s about breaking up content, but in a way that keeps it connected. It’s also about making the design visually varied, and drawing the reader’s attention to the right points.

In text-heavy designs (like this assignment), graphics and headings are often used to pace the reader’s progress through the text, reducing fatigue and (hopefully) boredom. Here’s an example of how a magazine feature might be paced by alternating text and images:

Pacing

The need for pacing depends on the type of project. For example, most novels contain no pacing other than chapter headings — they are simply a stream of text.

However, publications like magazines and textbooks are often designed so that every one or two pages there is an image-heavy page to pace and illustrate the surrounding text. Ads are sometimes used in magazines to pace different features.

In the film scene, the blocks of vertical light in the centre help to pace the composition. Without these elements, the two areas of focus — the staircase and the conversation — would feel separate and disconnected. We’ve removed these pacing elements in the second image, so that you can see for yourself.

Pacing with visual elements

Lack of pacing when visual elements are removed

In conclusion-

Visual principles are powerful tools for us as designers, because they work with how people naturally see the world and interpret visual information. In each design brief you work on, think actively about how to use them, and how each principle could support the goals of the project.

For exercise #3 you’ll examine a poster design by Josef Müller-Brockmann, and try to identify how it uses visual principles.

Instructions for Exercise ︎

1

Analyse this poster design

Pictured below is a poster by the twentieth-century Swiss graphic designer Josef Müller-Brockmann.

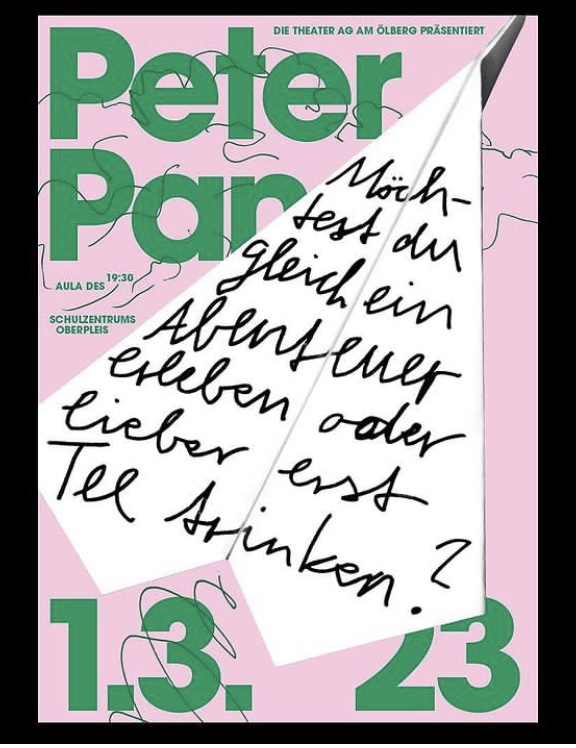

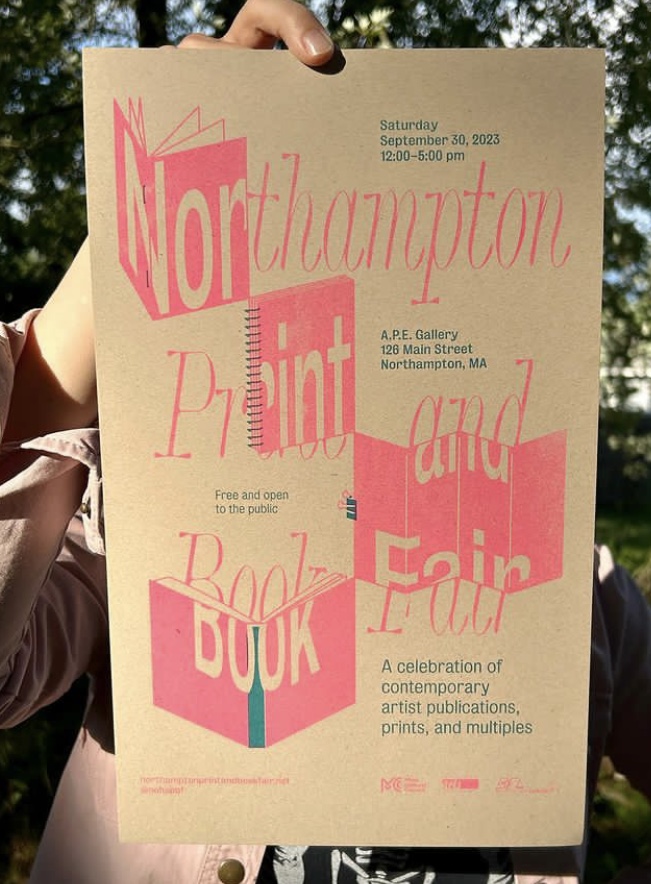

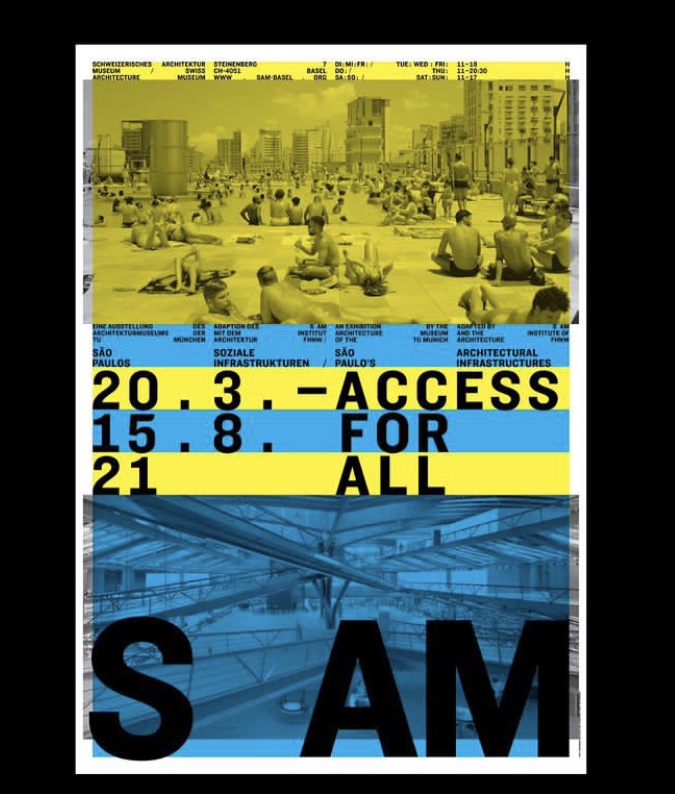

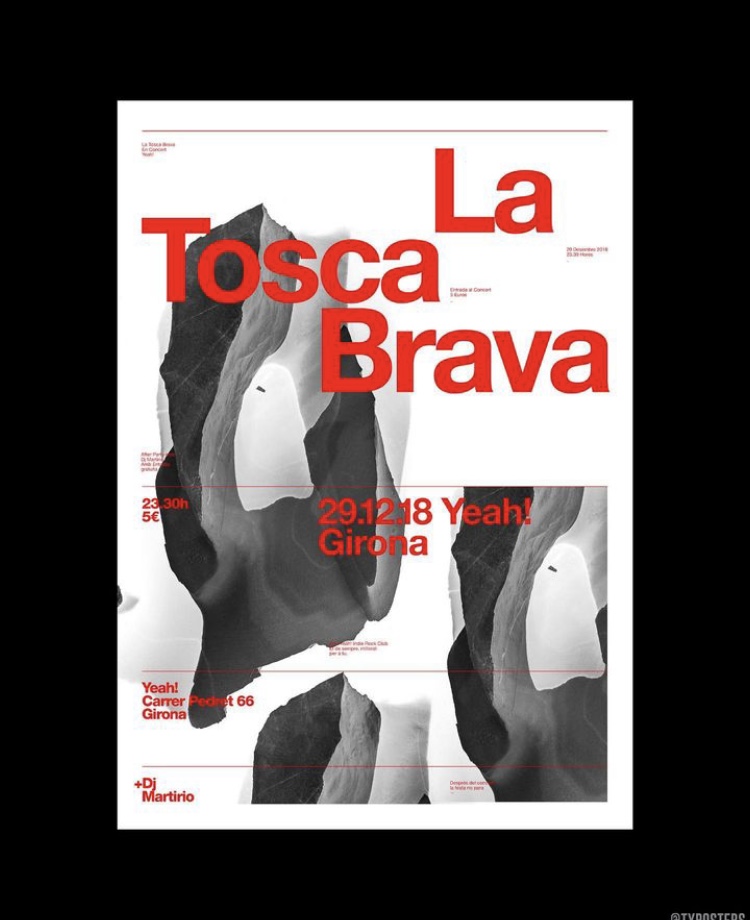

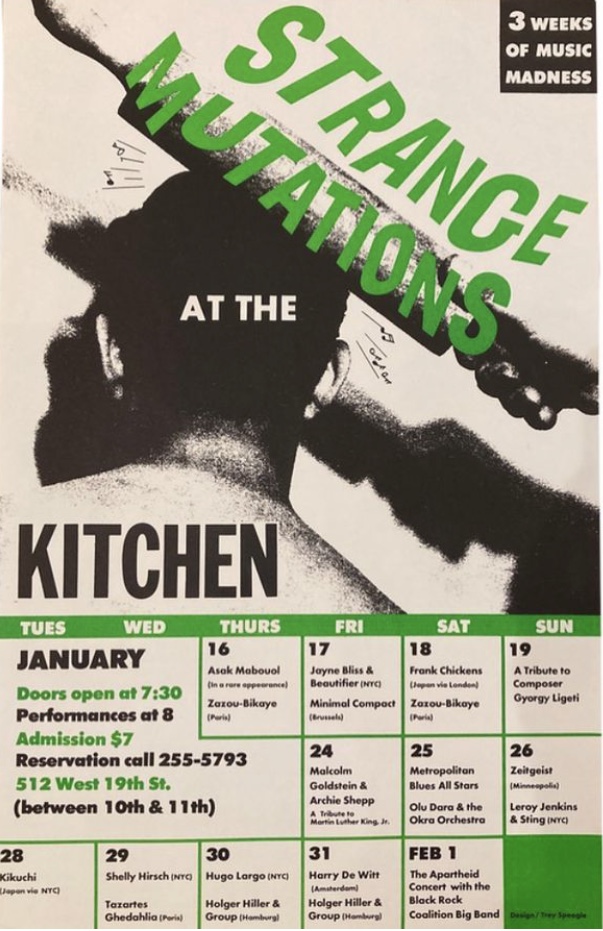

Below are 6 contempoary posters

Study them carefully, and write down how you think they use the visual principles introduced in today’s lecture.

Here they are again:

- Proximity and grouping

- Visual hierarchy

- Spacing

- Alignment

- Contrast

- Balance

- Repetition and consistency

- Pacing