Introduction

Color laser printers can create around a million colors. Humans can see around seven million of them. Computer screens can display over 16 million.

Today we will focus on what color is, the difference between additive and subtractive color mixing models, and the psychological, cultural, and ethical issues surrounding color.

What is color?

We could answer it in terms of:

︎ color physics (waves of light)

︎ aesthetics (which colors and combinations look nice)

︎ emotion (how colors make us feel)

︎ meaning (what different colors signify in nature and culture)

︎ function (for example, which colors aid clear communication)

︎ accessibility (certain color combinations can’t be seen by some people)

︎ ethics (for example, too many bright colors can cause sensory overload for some people)

These different indicate that, as a whole, color is best defined as an experience.

The color “blue” as we experience it isn’t actually “out there” in the world. Blue is a representation of something about the world, created by our brains, in response to a given frequency of light meeting our retinas. We then invest that perceptual experience with aesthetic, emotional, and cultural meaning.*

And because an experience of color is formed through the physical, neural, and psychological processes of each individual person, color can also be highly subjective.

When we make color choices as designers, we therefore need to navigate not only the physical and technical aspects of color, but also what colors mean aesthetically, emotionally, naturally, culturally, functionally, and ethically.

* The phenomenology of color is interesting, but very complicated. You can read more in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

Color physics and color mixing

The light waves out of which we form an experience of color can be perceived either directly from a light-emitting source like a computer screen, or indirectly via reflection off of another surface.

Almost all of our visual experiences of the world (beyond computer screens) are of reflected light.

The perception of emitted light

The perception of reflected light

These two ways of perceiving light waves lead directly to two different models of color mixing: additive and subtractive.

On the one hand, when we look at a computer screen, we are experiencing additive color mixing. Red, green, and blue light is mixed in different proportions to create any of 16.7 million possible colors. 0% 0% 0% is black; 100% 100% 100% is white.

On the other hand, when we look at a surface from which light is being reflected, we are experiencing subtractive color mixing. The properties of the surface absorb certain wavelengths of light, “subtracting” that color from the light that is reflected back and perceived by the retina.

In turn, additive and subtractive color mixing leads us to the two main color models we need to know about as designers:

︎ RGB (red, green, blue), which is used for digital design

︎ CMYK (cyan, magenta, yellow, black), which is used for printed design.

Aesthetics, emotion, and meaning

let’s consider how different colors come to assume aesthetic, emotional, cultural, and natural meanings.

-What is it that makes us describe one color as “beautiful”, and another as “horrible”? How and why do we form value judgements about waves of light?

Our attitudes towards color come from many many places – below are a few of the most discussed.

1. How we’ve evolved biologically to interpret particular colors

Image credit: Erwan Hesry

Since we can’t see in the dark, we might associate black with danger. Conversely, we might find bright, vibrant colors attractive, because they often indicate sources of food, and indirectly, sources of water.

2. What others taught us when we were young

For example, we might have been taught that red berries can be dangerous. In many western cultures, Colors is gendered like blue for boys and pink for girls.

3. Memories of colors

These will be especially powerful if they evoke important experiences in someone’s past. For example, the house where we grew up might have been painted purple, which could make purple a nostalgic experience.

4. Associations with the color of objects

For example, a particular kind of yellow might make us think of bananas, and a specific shade of green might make us think of grass. (These associations are often used to help describe paint colors.)

Those objects will also have secondary associations. For example, banana-yellow and grass-green might make us think of summer, fresh air, health, and exercise.

5. The cultural meaning of particular colors or color combinations

For example, many westerners associate red and green with Christmas, and in Japan, red and white are traditionally associated with happiness and joy.

6. Historical associations

For example, the combination of black, white, and red might remind people of the flag of Nazi Germany — especially because it persists in the present visual experiences of history books and documentaries.

7. Brand associations

For example, the combination of particular shades of red and yellow might remind us of McDonald’s, or greeny-blue could remind us of Tiffany & Co.

What this list should tell us as designers is that colors always have associated meanings. Those associations can be helpful and creative, but there is also always a risk that we trigger unintended associations.

Functionality, accessibility, and ethics

As designers, it’s important for us to be aware of how our color choices affect others —culturally and physically. (Those with non-typical color vision)

For example, as many as 1 in 10 boys and men have some form of colourblindness, the most common being red–green and green–blue. This may make it hard to distinguish those colors from one another when they’re combined, or make it unclear whether a color is red or green in isolation.

In turn, this should make us reconsider how we use these colors and combinations in our designs — particular if those colors are used on something important or functional.

More broadly, those with impaired vision may struggle to read text if it is set using colors with a low “contrast ratio”. The highest contrast ratio is black on white. The further each color moves from black and white, the lower the contrast ratio gets.

Other ethical questions relate to the color associations we discussed earlier. For example, some color combinations have strong associations with particular countries, cultures, movements, and communities.

The trans pride flag, for instance, uses a very specific combination of white, pink, and blue. Before using that color palette, as designers it is our responsibility to consider whether our application of it could lead to unintended interpretations, or cause unintended offence.

Technical Color

Color wheel. The color wheel simply provides a model for describing the relationship between different hues.

The names of the standard types of color palette are descriptive of the relationships between the colors. So a palette with hues that are next to each other on the color wheel is called “analogous”; one where the hues are from opposite sides of the color wheel is called “complementary”; etc.

Types of color palette

Analogous color palette

Formed of hues that are next to each other on the color wheel.

Example shown:

︎ pink, red, orange

Complementary color palette

Formed of hues that are opposite each other on the color wheel.

Example shown:

︎ pink, green‑cyan

Split–complementary color palette

Formed of a base hue, and then two hues from the opposite side of the color wheel.

Example shown:

︎ pink (base), green, cyan

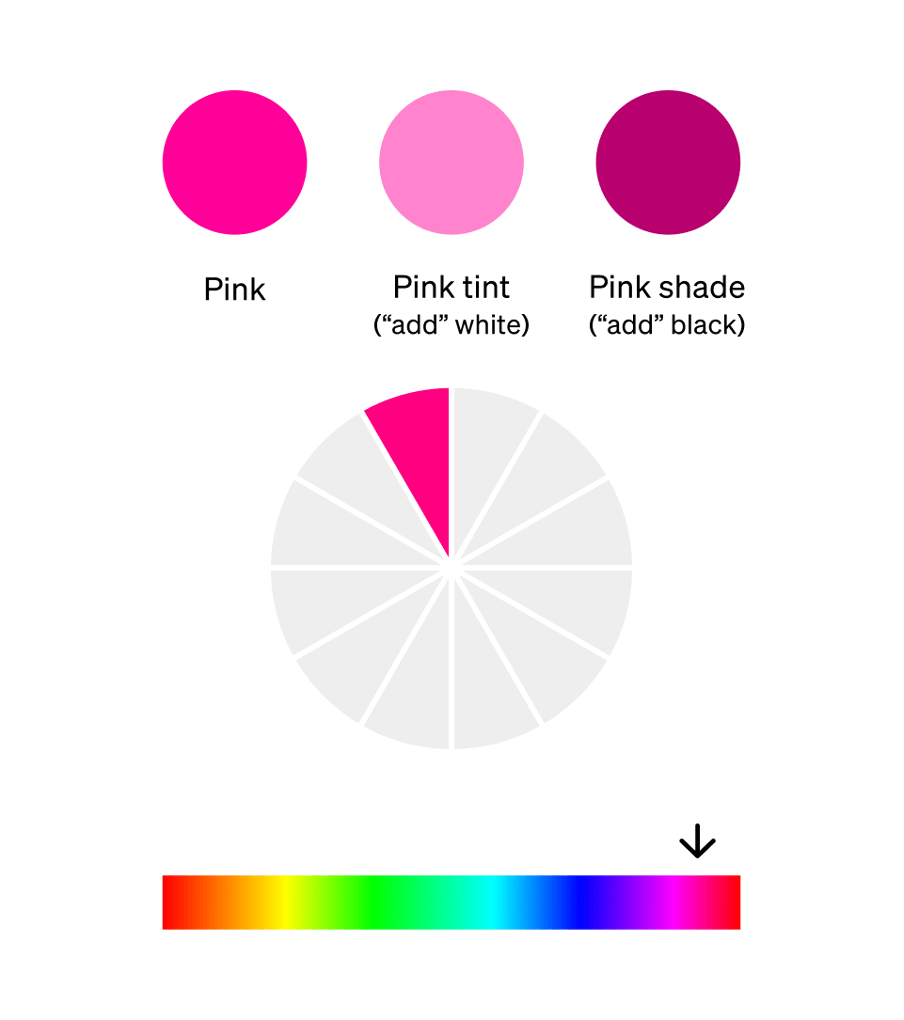

Monochromatic color palette

Formed of tints and shades of a single hue. Think of a tint as “adding” white, and a shade as “adding” black.

Example shown:

︎ pink, pink tint, pink shade

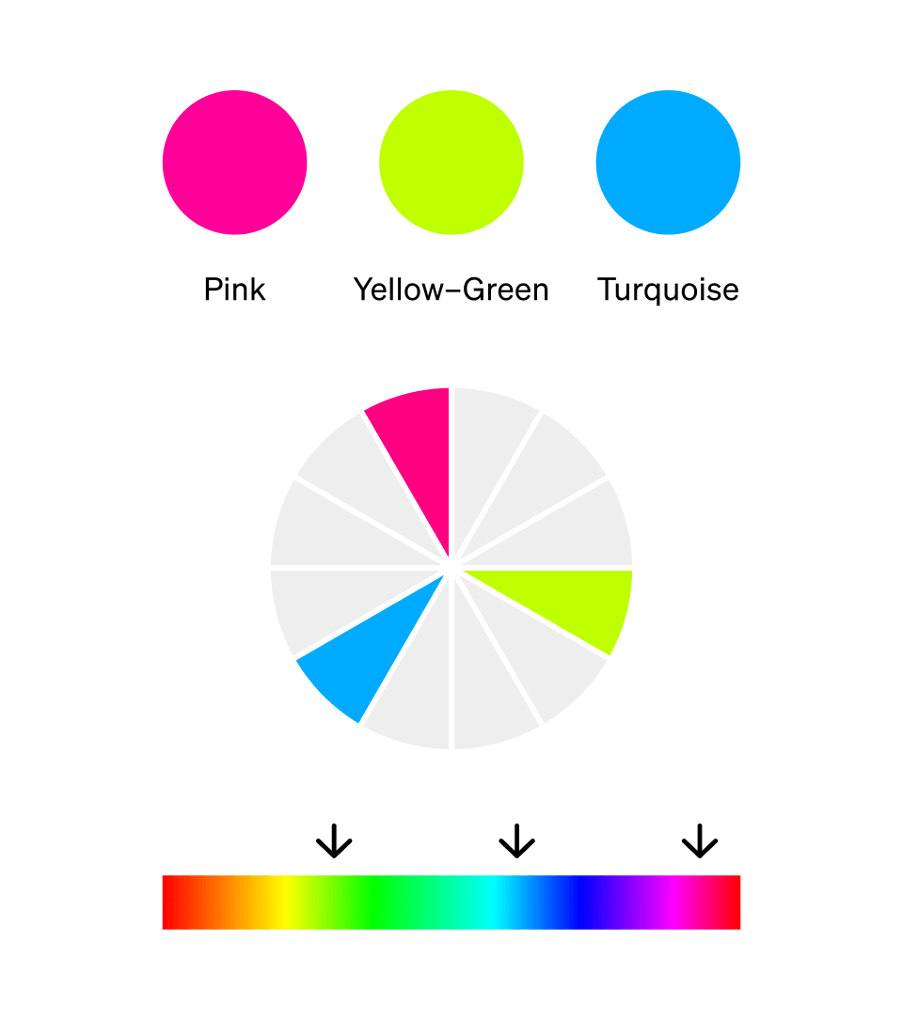

Triadic color palette

Formed of hues from three relatively evenly-spaced points around the colour wheel.

Example shown:

︎ pink, yellow‑green, turquoise

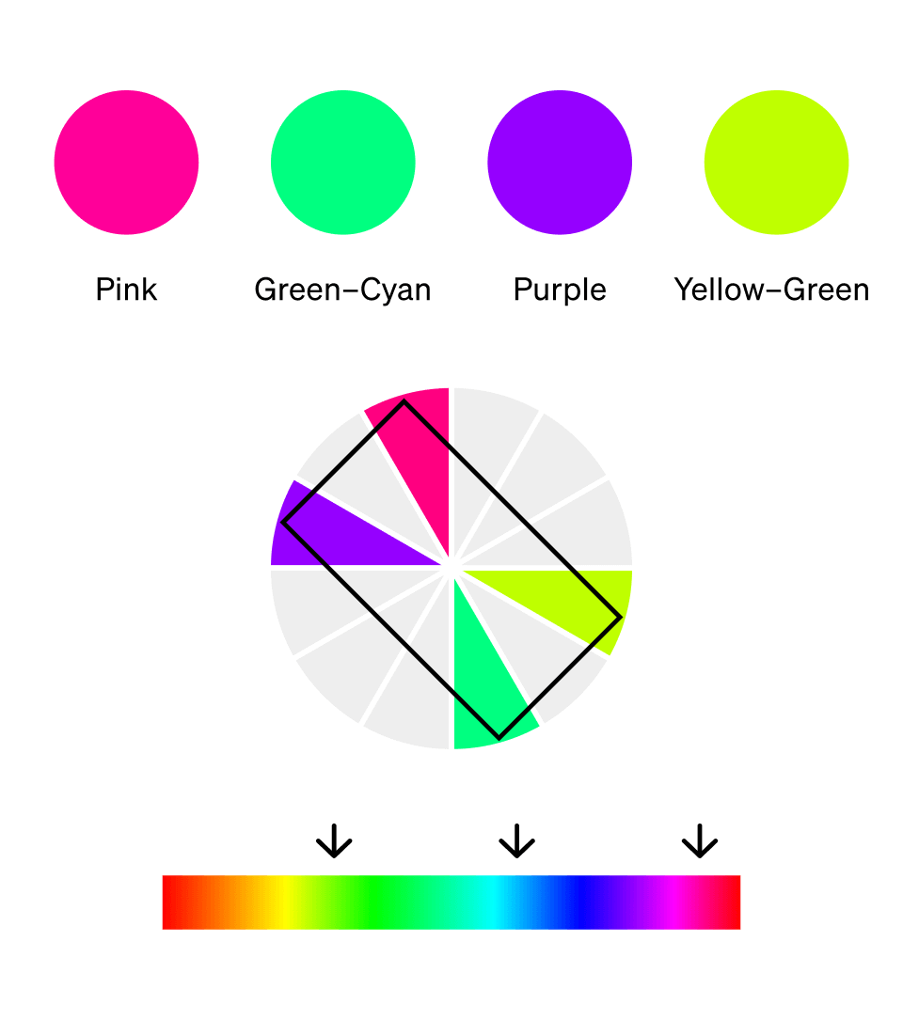

Tetradic color palette

Formed of two pairs of complementary hues, creating a rectangular shape on the color wheel.

Example shown:

︎ pink, green‑cyan, purple, yellow‑green

Technical Numbers

Depending on which piece of software you're using, you might see the numbers here in different sequences, or some might not be there. Here are the main things you can expect to see. These are all just different ways of encoding a color choice.Hex code

These are the codes used on the web to tell browsers which color to use. They begin with a hash, and then follow a RRGGBB format (red, green blue). This is called a hex code because the numbers are “hexadecimal”, so each number runs like this:0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F

RGB code

This is another way of encoding a color, except instead of using hexadecimal, each color (red, green, blue) simply runs from 0 to 100. So pure red is 100.0.0, pure blue is 0.0.100, etc.HSB or HSV code

That the hue, saturation, value model we explored earlier in this lesson.HSL code

This is slightly different from the HSV/HSB color model: the L here stands for “lightness”, and present a slightly different conceptual model for color mixing. Experiment and see if you can spot the differences in how it works!Opacity

All of the color modes above can store a fourth number besides red, green, and blue values: they can also store information about opacity. All color systems conceptualise opacity from 0 to 100, with 0 being completely transparent, and 100 being completely opaque.Opacity can be used to create layered effects, and it’s also a useful tool when building color schemes for user interfaces. Note, however, that not all image file types can store transparency information. The most important of these is JPEGs. In most software, transparent pixels will get saved as white pixels in JPEGs.